English translation of the book “Corruption” by David und Thomas Schirrmacher is launched at the Integrity Conference in Manila

The English edition of the Book “Corruption” by Thomas and David Schirrmacher within the WEA Global Issues Series has been launched during the Conference “In Pursuit of Integrity” in San Juan (Philippines) in which Thomas Schirrmacher gave a plenary speech „Corruption and Original Sin“. The conference was organised by ‘The Lausanne and World Evangelical Alliance Integrity and Anti-Corruption Network’ has the following board members:

The English edition of the Book “Corruption” by Thomas and David Schirrmacher within the WEA Global Issues Series has been launched during the Conference “In Pursuit of Integrity” in San Juan (Philippines) in which Thomas Schirrmacher gave a plenary speech „Corruption and Original Sin“. The conference was organised by ‘The Lausanne and World Evangelical Alliance Integrity and Anti-Corruption Network’ has the following board members:

- Dr Lazarus Phiri, Vice Chancellor of the Evangelical University in Ndola, Zambia

- Dr Cesar Vicente Punzalan III

- Dr David Bennett, Global associate Director for Collaboration and Conten, Lausanne Movement

- Dr Lloyd Estrada, Bible Engagement Advocate, WEA, formerly with Wycliffe Global Alliance

- Dr. Manfred Kohl, Canada

Interview with Thomas and David Schirrmacher

Bonner Querschnitte: Why should someone who is not corrupt or is not affected by corruption read your book?

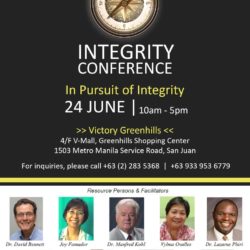

The invitation flyer of the conference © BQ/Warnecke

Thomas Schirrmacher: Corruption is not a private problem and is not a trivial offense. Corruption can kill, for instance, if poor quality replacement parts are installed in airplanes or if development aid in the form of funding for those starving is diverted for private use. Everyone is affected, or at least many are, even if for the most part they do not notice it directly or know about it directly. Everyone is actually in some way affected by it. However, around the world it is mostly the poorest of the poor who are afflicted by it, for instance when crucial funds are lacking for drinking water or medical care.

David Schirrmacher: Corruption is itself economic crime, but at the same time it is a permanent side effect of all other types of economic crime. Offshore accounts for illicit purposes, cartel agreements, human trafficking, organized illegal employment, forced prostitution, and insider stock trading would practically not exist if there were no bribes.

BQ: Is there something special about your book?

David Schirrmacher: It is compact! One less TV thriller and you are informed.

Thomas Schirrmacher: The book contains innumerable examples of corruption, all briefly explained. They are all very neatly arranged with one paragraph each, and there is a keyword above each one to indicate the type of corruption involved in each example.

David Schirrmacher: As the logos on the back show, the book is being used for campaigns by the International Society for Human Rights, Gebende Hände (Giving Hands), the Micah Initiative, and StoppArmut 2015 (Stop Poverty 2015) in Switzerland. It really is a book for people who want to bring about change!

BQ: Do you have a few numbers for us?

(from left to right): Bishop Efraim Tendero, Dr Lazarus Phiri, Bishop Dr Thomas Schirrmacher, Dr Manfred Kohl © Cesar Punzalan III, Manila

David Schirrmacher: The World Bank estimates that each year one trillion dollars flow through corrupt channels. To abolish extreme poverty (people who live on less than $1.25 per day), an estimated $60 billion would be needed per year. In large-scale industrial projects in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, it is rumored that there is bribe money that amounts to 3 percent of the contract value. International managers assume that corruption increases project costs by 10 percent on average.

BQ: What do corruption and morality have to do with each other?

Thomas Schirrmacher: Corruption is marked by its secrecy. For that reason, concealment as well as covering up, deception, lying, cheating, and betrayal of trust are always components of corruption.

David Schirrmacher: Up to the time of the financial crisis, circumventing laws, regulations, and morality for one’s own advantage seemed to many German citizens to be shrewd and understandable. However, through the experience of the global financial crisis, it became apparent that a small number of individuals acting immorally could endanger the livelihood of millions if not billions of people. For one individual who perhaps has one yacht more, there are millions who suddenly can no longer pay for food or lose their savings.

BQ: What was your actual motivation?

(from left to right): Bishop Efraim Tendero, Dr Lazarus Phiri, Bishop Dr Thomas Schirrmacher, Dr Manfred Kohl © Cesar Punzalan III, Manila

Thomas Schirrmacher: We took up the topic of corruption as human rights activists because a significant portion of human rights violations are made possible in the first place due to corruption or because criminal prosecution does not work owing to a corrupt justice system.

David Schirrmacher: An entire book could be filled documenting just how often it does not make sense to go after human rights violations when you don’t go against corruption at the same time.

Thomas Schirrmacher: Besides that, we think that convinced Christians are obligated to stand up against corruption. Pietism, which is the trajectory of belief in which we include ourselves, takes as its father Philipp Jakob Spener (1635–1705). He wrote in 1675 in his major work Pia Desideria (Pious Desires) about how terrible he found it to be that even Christians gain “an edge” through corruption which “make[s] it difficult … for one’s neighbor, indeed oppressing and bleeding him.” Old Testament prophets saw fighting corruption and greed to be the best way of protecting the poor and those who possess no rights. We can only endorse that.

BQ: Is corruption culturally conditioned? Is corruption something which humanity defines and condemns equally? Or does the definition of corruption depend so heavily on the respective historical moment in time and society that it is impossible to make any international comparisons?

Thomas Schirrmacher: In our opinion, corruption is something like torture, which is wrong always and everywhere, regardless of the culture in which it occurs. For instance, it does not belong in the same category as tax evasion, which can only be defined in a certain year and in a certain country and changes according to adjustments in tax legislation.

Bishop Efraim Tendero during his lecture © Cesar Punzalan III, Manila

David Schirrmacher: Surely, there are significant cultural differences in the understanding of public offices, for instance in how to deal with gifts, or with respect to the payment of civil servants. And naturally, there have been significant differences with respect to which types of corruption are punished and how this has been conducted, even if over the course of recent years there has been vast international harmonization relating to legislation. Nevertheless, apart from doubtful cases, there are many types of corruption which the majority of all of us mortals consider to be wrong and objectionable. This is seen at the latest when at the time of almost every revolution rulers are considered to be completely corrupt and there is a strong desire to place uncorrupt politicians in their stead. This shows that even in a very corrupt society there is a general awareness that corruption should not occur and that it damages society.

Thomas Schirrmacher: Egypt, for example, is a society ridden with corruption. Despite this, or specifically on account of this, Mohammed Mursi was able to become President of Egypt by promising to end corruption and to be there for the poor. The fact that the public already wanted to get rid of him after a year also had to do with the fact that he was shown to be as corrupt as his predecessor.

David Schirrmacher: The argument that combating corruption is cultural imperialism and that one has to accept that there are cultures in which making gifts to holders of office is simply commonplace actually lost its penetrative power in 2003 due to the fact that since that time 170 countries have voluntarily ratified the UN Convention against Corruption. This occurred in spite of the fact that the Convention went beyond anything existing up to that point as far as anti-corruption agreements in the USA and Europe were concerned.

BQ: How do you define corruption?

Participants of the Integrity Conference in Manila © BQ/Warnecke

Thomas Schirrmacher: As the abuse of entrusted power for one’s own advantage.

David Schirrmacher: Private advantage does have to be one’s own. It can have to do with a third party or an organization, for example one’s own political party. Bribery can occur with much more than just money or material donations. People can be bribed with offices, titles, honors, or promotions, with memberships, insider knowledge, or with sexual services.

BQ: Which specific actions can be taken against corruption?

Thomas Schirrmacher: An individual does not have to wait until there is a particular case where someone becomes corrupt. Rather, all systems have to be set up from the beginning in a way that takes corruption into account and protects against it. Surely there are many people who are not corrupt. However, they will not be bothered by such preventative measures, checks, and punishments. Everyone else should know from the start that resolute steps will be taken to address corruption.

Dr Lloyd Estrada, Moderator of the Integrity Conference in Manila, speaking © BQ/Warnecke

David Schirrmacher: There are important rules of thumb which need to be incorporated into every system and every company. For instance, rules of thumb are needed that unconditionally control visual inspection of documents and contain results (e.g., of purchased assets, of structures built, and of local events). Additionally, it should never be the case that only one person is responsible from beginning to end for a project or for procurement. Conversely, experience teaches that rotation and regrouping senior employees is not always the solution. Through these measures, corruption can also gradually spread throughout an entire system.

BQ: Can each of you add a specific suggestion?

Thomas Schirrmacher: Anti-corruption officers have been tried and tested (especially in agencies but also in companies and NGOs). However, they should be experienced auditors and know the actual running of their operations from the inside, along with all its secrets, i.e., they should not be chosen on the basis of political viewpoints or on criteria foreign to performance.

David Schirrmacher: A code of ethics should be available in written form, should be understandable, and should mention good reasons which likewise apply equally to everyone from the greatest to the smallest, name disciplinary consequences, indicate who are the points of contact, and mention the mediation committees. Additionally, it should be a living document which is communicated clearly and is repeatedly the object of discussions at all levels.

BQ: Thank you very much for the conversation.

- The invitation flyer of the conference © BQ/Warnecke

- (from left to right): Bishop Efraim Tendero, Dr Lazarus Phiri, Bishop Dr Thomas Schirrmacher, Dr Manfred Kohl © Cesar Punzalan III, Manila

- (from left to right): Bishop Efraim Tendero, Dr Lazarus Phiri, Bishop Dr Thomas Schirrmacher, Dr Manfred Kohl © Cesar Punzalan III, Manila

- Bishop Efraim Tendero during his lecture © Cesar Punzalan III, Manila

- Participants of the Integrity Conference in Manila © BQ/Warnecke

- Dr Lloyd Estrada, Moderator of the Integrity Conference in Manila, speaking © BQ/Warnecke

- View of the audience during the speech of Thomas Schirrmacher © BQ/Warnecke

- Thomas Schirrmacher during his speech © BQ/Warnecke